Everyone should have the opportunity to achieve good health. But, as Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones explains, that’s often not the case. The Urban Institute recently collaborated with the previous president of the American Public Health Association to bring to life her analogy of the “cliff of good health” in this whiteboard animation.

Accounting for nearly 18 percent of US gross domestic product, our national health care system directs an astounding sum to the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff (acute medical care), and relatively little to the net or fence (secondary and primary prevention). And until recently, it was virtually unheard of for the health care sector to try to move people away from the edge of the cliff by attending to social determinants of health like hazardous housing, underfunded schools, or a lack of public transportation. We have focused efforts on individual care, rather than on population health and well-being.

But that is beginning to change.

In November, the US Department of Health and Human Services secretary Alex M. Azar announced that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services would soon introduce new mechanisms and programs to pay for non-medical services:

“What if we went beyond connections and referrals? What if we provided solutions for the whole person, including addressing housing, nutrition, and other social needs?”

Although his speech was short on details, it’s clear that our country’s top leaders consider the social determinants of health too important to ignore.

But as we’re learning, there’s more we can do to go upstream in our interventions.

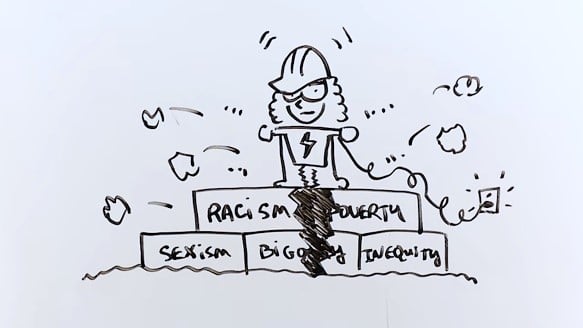

As the video illustrates, the cliff of good health is more complex than one might think. In addition to the social factors that push people closer to the edge, there are systemic, structural, and historical forces that have barred certain groups and populations from the opportunity to achieve good health. For example, while the discriminatory zoning practices and hiring policies of 50 years ago have (mostly) been abolished, the effects of those historical barriers can still be seen and felt today.

Health inequities are found across multiple dimensions, including education and income level, gender, race, and ethnicity—even someone’s zip code. Many of these health differences appear early in life and are difficult to reverse.

Indeed, Jones’s distinction between the social determinants of health and the social determinants of equity is central to her bigger point: simply redirecting resources to other sectors to address the social determinants of health won’t cut it. To see real change in our country’s health outcomes, we need to dismantle the tangled systems of structured inequity, like racism and sexism.

But throughout our work with her, we were struck by Jones’s optimism. Policymakers, private industry, and practitioners are actively seeking solutions to promote well-being beyond improving our health care system (no small job). They’re trying to connect the dots on social services spending and health outcomes to introduce policies and programs that bolster health for individuals, families, and communities.

And we’re seeing the beginnings of a movement to ensure those policies and programs are built around equity—not as an afterthought, but as a deliberate pillar of policy design.

Health isn’t just about what happens in a doctor’s office, or even at the dinner table or the gym. We all have work to do to make sure that all Americans have the opportunity to achieve good health.

∎